Hyperinflation: trauma and its reconstruction

20 June 2025

By David Barkhausen

Memories of hyperinflation live on in public debates on money. In the case of Germany, the trauma of 1923 is widely seen as the source of the country’s preference for fiscal discipline and stability-oriented central banking. Historical analysis sheds new light on the collective memory and its genesis.

How we think, feel and talk about money is shaped by the past. And depending on where we grow up monetary history looks different and is remembered differently. The German public debate and the country’s preference for policies that prioritise monetary stability is an illustrative example of this.[1]

Although Germany was shaken twice by hyperinflation in the twentieth century, it is the trauma of the 1920s that has “burned itself into [German] collective memory”[2]. It prominently lives on not only in family stories but newspaper headlines and political debates. And among those, it is widely acknowledged that this trauma continues to haunt the population and fans fears of inflation and debt.[3]

But was it actually the traumatic experience itself that left such a deep and long-lasting impression on people in Weimar Germany? And was the subsequent preference for fiscal discipline and stability-oriented central banking then transmitted from one generation to the next?

There is another way to look at our perception of monetary history. Could it also be that the way politicians, academia and the media made sense of the trauma in the decades following which influence how we remember the event a century later?

After all, many European countries went through similar bouts of hyperinflation[4]. Yet, it appears that only in Germany did history produce such a vivid collective memory and powerful policy impact.

Two sources of historical memory raise reasonable doubt about the dominant interpretation that Germany’s preference for stability policy was spawned in 1923:

- the personal accounts of people who experienced hyperinflation;

- the political debates that ensued in the subsequent decades.

The first source draws on the analysis of 179 memoirs, which makes up a significant share of all personal recollections and – so far – is the largest text corpus of autobiographies relating to the early 1920s in Germany. It includes the writings of politicians, journalists, artists and other public figures, such as former chancellor Heinrich Brüning and philosopher Walter Benjamin. However, the sample also includes the writing of regular working people, such as farmers Sophie and Fritz Wiechering.

The second source consists of all Bundestag debates and parliamentary speeches made between 1949 and 2022. Of those more than 55,000 speeches made by individuals from all corners of the German political spectrum, 272 mention the Weimar hyperinflation and have therefore fed into the analysis.

Though sizeable, the collection of memoirs and speeches does not fully represent how German society felt about, and remembered, hyperinflation. Nevertheless, both sources provide significant qualitative insights for studying the collective memory of inflation trauma.

Memories of hyperinflation in personal memoirs

How did Germans experience hyperinflation in 1923? As money lost its value within hours, people tried to spend their wages as quickly as they could. Food and tradable goods were in high demand. And the relationship between time and value changed dramatically in Weimar society. Undoubtedly, this could be traumatic.

In numerous studies, historians have shed light on economic hardship and profound stress among the population. While many Germans were freed of debts, hyperinflation obliterated the value of savings and financial assets. Anyone with a fixed income – pensioners, widows, but also public officials or landlords – faced impoverishment.

That spurred social resentment, fuelled crime, contributed to political turmoil[5] and created an atmosphere of uncertainty, instability, chaos and despair. Based on these accounts, it is easy to imagine an enduring traumatic impact on the population.[6]

Furthermore, studies show that personal experience of high inflation does affect preferences, expectations, and behaviour – even across generations.[7]

However, the question remains: to what extent did the experience of hyperinflation directly influence people’s economic memory and their policy preferences?

If today’s understanding – that hyperinflation had a direct impact on economic culture and the preference for stability-oriented policy in Germany – holds true, this would suggest a stable and more or less uniform memory of 1923. We would expect a consistent corelation between trauma and stability policy in the eye-witness accounts of those who lived through hyperinflation. However, the memoirs do not bear this out.

Although an in-depth view of personal recollections reveals that many authors did remember hyperinflation as negative or traumatic, almost half of the memoirs mention it only in a few sentences, or even not at all. Some memoirists even go so far as to characterise 1923 as a cheerful period or emphasise positive aspects of inflation such as debt relief.

Indeed, a few authors linked hyperinflation to the lessons of restrictive fiscal policy and central banking. Among them are historically notable figures such as chancellor Brüning, banker Erwin Hielscher or economic journalist Volkmar Muthesius. But, overall, one cannot identify any dominant or coherent political reading of the events in 1923 in the autobiographies.

Had the experience of hyperinflation created an overwhelming preference for stability policy, we would expect a significant portion of the memoirs to remember 1923 in this light. Yet, most authors – about 70% – do not even discuss the reasons and causes of hyperinflation at all.

And even if people did experience trauma, there is notable indication within the memoirs that the transmission from one generation to the next could have suffered from failing memory. Some memoirists – including Hielscher, but also former finance minister Hans Luther – claim that people would poorly remember or understand the events they lived through.

In summary, it appears the experience of hyperinflation in 1923 did not immediately birth the policy lessons engrained within collective memory today – at least not exclusively. So how else could we explain that prevalent link?

Tracing trauma in the Bundestag

Again, the academic literature offers a good starting point. According to several studies, today’s vibrant collective memory emerged not without help. Next to family stories or other personal recollections, it was how politicians, institutions and publicists made sense of hyperinflation in the following decades that anchored the event in collective memory and shaped its guise. As history is always a product of the present, so was this reconstruction. Such recollection and the lessons drawn within the public debate – research indicates – live on and continue to influence how people remember today.[8]

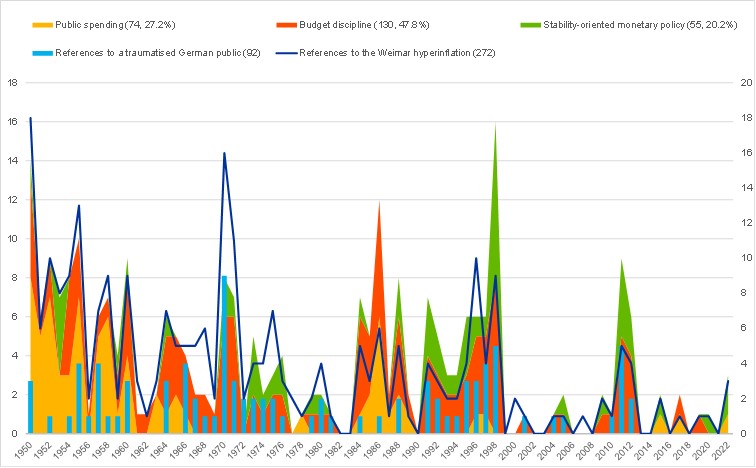

The analysis of German parliamentary debates strengthens the case made by those findings. Examining all speeches made in the Bundestag since 1949 that mention “inflation” (or synonyms) we check for monetary and fiscal policy proposals speakers brought up when invoking memories of 1923.

This analysis makes for several striking observations: Firstly, the link between hyperinflation and stability-oriented monetary policy occurred only when the Bundestag debated questions of currency and monetary stability; and secondly, we see a conspicuous shift in the fiscal proposals mentioned in liaison to the Weimar memory (Chart 1).

Perhaps surprisingly, during the very early years of the Bundestag speakers used hyperinflation more often as an argument for public spending than for fiscal discipline. And that was across the political spectrum, including members of the Christian-democratic CDU and the communist KPD. Their line of argument suggested the need to expand support for those still suffering the lasting effects of 1923. In the following decades, the call for fiscal discipline then slowly but surely gained ground, without yet becoming dominant. This picture changed from the late 1980s onwards. Only then did fiscal discipline emerge as the predominant policy proposition tied to the Weimar memory.

As such, it played a particularly prominent role in the debates on European monetary integration during the 1990s and the euro area crisis in the 2010s. During both periods, policymakers, especially those from the CDU/CSU and FDP, called for tight fiscal rules with reference to hyperinflation. Both times, they pointed to the traumatised German public when arguing for anchoring and defending fiscal precautions in the name of monetary stability, as well as when making the case for an independent, stability-oriented central bank in the common European legal framework.

Again, these findings are striking as today’s understanding would suggest a historically constant, uniform conflation between hyperinflation and the lessons of stability policy.

Chart 1

References to the Weimar hyperinflation in Bundestag speeches

Source: Barkhausen & Teupe (2025), Barkhausen (2025).

Why understanding monetary culture matters

More than a century after the event, the spectre of the Weimar hyperinflation continues to haunt the population. Time and time again, its imagery – wheelbarrows filled with cash, people burning banknotes as fuel and paper kites worth billions – resurfaces in the public debate. And it is this spectre that often serves as an explanation for the German fear of inflation and the national preference for fiscal stability.

But how come we remember the event the way we do? Was it foremost the experience of hyperinflation that taught German society the lessons of stability-oriented policy which then became engrained in collective memory? The empirical material presented here suggests otherwise. There is good reason to assume that, rather than the traumatic event itself, it is the ways it has echoed through domestic and European debates that shaped collective memory, and as a result influences also today’s thinking.

There are at least two reasons why we should be interested in the roots of our economic beliefs.

First, in a culturally diverse currency union, it is essential to know about and understand each other. Sentiments and sensitivities do exist – they shape political debates and they influence decisions. So they demand sufficient understanding and empathy. Regardless of where our economic ideas and shared notions of the past come from, we must acknowledge their existence. After all, what policymakers do and say, some may deem necessary and legitimate while others could see the same as an onslaught against their history, values and identity. The ECB must consider this if it wants to communicate effectively and maintain public trust.

Second, it is equally important to understand ourselves. And that includes the roots of our beliefs and preferences. In this regard, we need to remember that shared stories of the past are always a product of the present. They focus and omit. They come with a bias. And not seldomly, they serve specific purposes. That does not take away any of the merit that historical lessons may hold. But at the same time, understanding and questioning such collective notions offers us the opportunity for open debates. And that helps us make better decisions in the future.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

Check out The ECB Blog and subscribe for future posts.

For topics relating to banking supervision, why not have a look at The Supervision Blog?

References

Barkhausen, D., 2025. Trauma as a Tool: Hyperinflation Narratives in German Fiscal Policy Debates on European Monetary Integration. Journal of Common Market Studies, preprint.

Barkhausen, D. & Teupe, S., 2025. The German Inflation Trauma: Weimar’s Policy Lessons Between Persistence and Reconstruction. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 245(3), pp. 269–332.

Blyth, M., 2013. Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Botsch, M. J. & Malmendier, U., 2020. The Long Shadows of the Great Inflation: Evidence from Residential Mortgages. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14934, pp. 1-81.

Braggion, F., Meyerinck, F. v., Schaub, N. & Weber, M., 2025. The Long-term Effects of Inflation on Inflation Expectations. Chicago Booth Research Paper No. 23-13, pp. 1-44.

Ehrmann, M. & Tzamourani, P., 2012. Memories of high inflation. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(2), pp. 174-191.

Feldman, G., 1993. The Great Disorder: Politics, Economics, and Society in the German Inflation, 1914-1924: Politics, Economics and Society in the German Inflation, 1914-24. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Hanke, S. & Krus, N., 2012. World Hyperinflations. Cato Institute Working Papers, pp. 1-18.

Hayo, B. & Neumeier, F., 2016. The social context for German economists: public attitudes towards macroeconomic policy in Germany. In: G. Bratsiotis & D. Cobham, eds. German macro: how it’s different and why that matters. Brussels: European Policy Centre, pp. 64-72.

Howarth, D. & Rommerskirchen, C., 2013. A Panacea for all Times? The German Stability Culture as Strategic Political Resource. West European Politics, 36(4), pp. 750-770.

Howarth, D. & Rommerskirchen, C., 2017. Inflation aversion in the European Union: exploring the myth of a North–South divide. Socio-Economic Review, 15(2), pp. 385–404.

Hüther, M., 2021. Der lange Schatten der Hyperinflation. List Forum für Wirtschaft- und Finanzpolitik, 46, pp. 273–298.

Johnson, P., 1998. The Government of Money - Monetarism in Germany and the United States. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Lindenlaub, D., 2010. Deutsches Stabilitätsbewußtsein: Wie kann man es fassen, wie kann man es erklären, welche Bedeutung hat es für die Geldpolitik?. In: B. Löffler, ed. Die kulturelle Seite der Währung. Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 63-100.

Malmendier, U. & Nagel, S., 2016. Learning from Inflation Experiences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(1), pp. 53–87.

Malmendier, U. & Wellsjo, A. S., 2023. Rent or Buy? Inflation Experiences and Homeownership within and across Countries. The Journal of Finance, 79(3), pp. 1977-2023.

Mee, S., 2019. Central Bank Independence and the Legacy of the German Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neyer, U. & Stempel, D., 2023. Hyperinflation, kollektives Gedächtnis und Zentralbankunabhängigkeit. Wirtschaftsdienst, 103(2), pp. 94-97.

Schieritz, M., 2013. Die Inflationslüge. Wie uns die Angst ums Geld ruiniert und wer daran verdient. München: Droemer Knaur.

Shiller, R., 1997. Why do people dislike inflation?. In: C. Romer & D. Romer, eds. Reducing inflation: motivation and strategy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 13-70.

Taylor, F., 2013. The Downfall Of Money. Germany's Hyperinflation And The Destruction Of The Middle Class. New York: Bloomsbury.

Teupe, S., 2022. Zeit des Geldes. Die deutsche Inflation zwischen 1914 und 1923. Bielefeld: transcript.

Distribution channels: Banking, Finance & Investment Industry

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.

Submit your press release