Bombs and chaos no bar to voters

By David Beresford in Johannesburg

27 April 1994

South Africans defied organisational chaos, personal hardship and long queues to throng polling stations yesterday for the historic all-race election that crowned their long march towards democracy.

While the authorities were under growing pressure last night to extend the three-day poll after serious problems in the first day of voting, the momentum for freedom looked unstoppable, with a new nation coming into effect at the stroke of midnight when the old flag was lowered and the new constitution took effect.

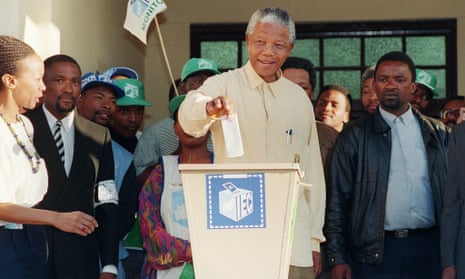

“Today is a day like no other before it … today marks the dawn of our freedom,” said Nelson Mandela, the African National Congress leader who is expected to become the country’s first black president. Mr Mandela spent 27 of his 75 years in jail for fighting apartheid.

“Years of imprisonment could not stamp out our determination to be free. Years of intimidation and violence could not stop us and we will not be stopped now,” he said.

President FW de Klerk, whose decision in 1990 to abandon apartheid, opened the way to the new South Africa, said: “I wanted this election to take place … that is what I have been working for.”

Around the country, the infirm, elderly and sick defied both a rightwing bombing campaign and widespread problems at polling stations in an extraordinary demonstration of hunger for the franchise.

Continue reading.

Eyewitness: cheers, tears and God Bless Africa as the new flag is raised

By Jonathan Steele in Cape Town

27 April 1994

With cheers, tears, and a multitude of hugs, the flag of white rule in South Africa was ceremonially lowered last night, three and a half centuries after the first European settlers landed near the Cape of Good Hope. With it ended the last act in the decolonisation of Africa and the end of the dream of a European empire which would stretch, in Cecil Rhodes’ phrase, “From Cairo to the Cape”.

A multiracial crowd of several hundred gathered shortly before midnight outside the provincial administration buildings to watch the new flag replace the old. On the balcony a choir sang the old “national” anthem, Die Stem, and then as the new flag went up, the first verse of the new anthem, God Bless Africa.

At the same time, an interim democratic constitution came into force as South Africans of all colours headed into a second day of elections signalling an end to more than three centuries of white domination.

“I am here to see this moment of history,” said Ishmail Jacobs, standing with a group of fellow Muslims. “It may be sad for some people, but my forefathers had nothing to do with the old flag.”

“I’ve watched the Berlin Wall come down on television, and all the other changes in Europe”, said Albie Sachs, one of the veterans of the anti-apartheid struggle. “It’s so nice that this change is happening here at home in our country.”

Even an Afrikaner policeman standing discreetly with his colleagues below the building was pleased. “I am glad that the government eventually took people into account. This is the people’s flag.”

Similar ceremonies were held in the capital cities of South Africa’s eight other new provinces, but none had as deep a resonance as the one in the Cape, the cradle of white minority rule on the toe of Africa.

Outside parliament, people formed a conga line and danced around a statue of the Boer general, Louis Botha. At the legislature, boisterous African National Congress supporters chanted Nelson Mandela’s name and waved ANC banners.

The country’s old standard, featuring the flags of Britain and two Boer republics set against an orange, white and blue field, was first raised outside parliament on 31 May 1928. It incorporated symbols of imperialism and settlement but there was no African element.

The new flag, designed by a multiparty committee, is not beautiful. It is like a letter Y on its side in six different colours, and South Africans are already calling it the Y-front. “It’s a mess,” conceded Albie Sachs.

But no one seemed to mind last night. What mattered was not the design but the change that it represents.

Vote of the century opens era of hope

By Gary Younge

28 April 1994

As dawn broke over Zone 9 of Meadowlands, Soweto, yesterday, the Mwale family was preparing for power.

First there was water to boil since the rumour had spread that the rightwing AWB might poison Meadowlands’ main tank. Esther Mwale said “most people with sense” in Zone 9 were boiling water.

Then, there was the huge pot of mealies – a staple of the township diet – to cook. On Tuesday, Granny had waited seven hours to cast her vote and they had had to bring her dinner while she queued. If there were long delays today, it would be her turn to come to the rescue.

Finally, there were the ID documents to find. No one could say the Mwales were not ready for democracy. As they set off at 7am, joining a human stream of hundreds on the main road, it seemed that all of Zone 9 had the same idea; first watch Nelson Mandela cast his vote in Durban on the television and then get down to the polling station at the Maponyane school quickly to beat the rush.

The clientele of Johannes’ shebeen (township bar) had discussed this eventuality the night before. At the beginning of the evening, Jacob’s solution to avoiding Tuesday’s chaos was to get there early. A couple of hours and a few beers later, the prospect of waking up at 5am and queueing for two hours looked increasingly unattractive.

Mzimasi suggested going to vote in a white suburb, where the queues would be shorter, but nobody knew anyone with a car who could take them.

Johannes said he was voting ANC “for his children”. But nobody else was prepared to say how they would vote. The talk was of logistics, not politics. Nevertheless, the sight of a white woman, who had cast her vote abroad, saying tearfully on television, “I’m just scared about the future,” aroused some fierce emotion.

Continue reading.